When I used to work as an associate at a large Social Security Disability firm, the usual way for attorneys there to review client files in preparation for covering hearings was to use a standard desktop computer to open the client’s scanned evidentiary documents and manually type out their case notes. Today, I’d like to share a method for case review and note-taking that I gradually developed while working as an associate. This method utilizes the relatively new technologies of tablet computers (for reviewing records) and advanced dictation software (for note-taking) in order to maximize speed and efficiency in completing case reviews.

Tablets

The main advantages to reviewing client records on a tablet rather than a traditional desktop monitor are increased portability and improved visual display. The benefits of portability are obvious. As for the visual display, most desktop monitors are only able to be oriented in a “landscape” orientation, while the majority of a client’s medical records will appear in a “portrait” orientation. This means that reviewing medical records on a desktop forces the user to choose between excessive clicking and scrolling (if the record viewer zoom is maximized, and thus only a portion of each page is displayed) or excessive squinting at the screen (if the record viewer zoom is minimized). See examples below.

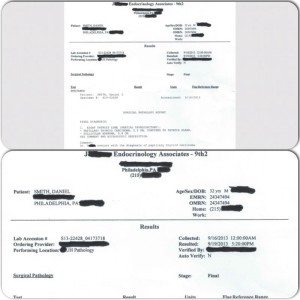

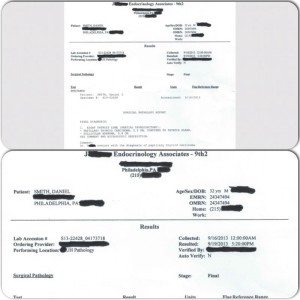

Sample medical record in portrait orientation as seen on a tablet

This problem may seem minor if the user is only reviewing a few documents, but since a typical client’s evidentiary file can contain hundreds if not thousands of pages of medical records, it can quickly turn into a major obstacle to an efficient review of records. With a tablet, however, records can be viewed in their original size and orientation depending only on how the device is being held in the user’s hands, which greatly expedites the entire review process.

Besides the special security precautions required when storing client files on a portable device, the only issue I’ve encountered with using my tablet (an iPad 2) to review records is the matter of compatibility.

A sample medical record in two different landscape views, as might be seen on the typical desktop computer monitor. At top, the zoom is minimized to view the entire page, but notice how much space is wasted on the sides of the monitor and how small the text ends up. At bottom, the zoom is maximized, but the screen is only big enough to display half the document at any one time. Thus, this would require a lot of page scrolling and wasted time/effort.

At least with my device, I can’t navigate SSA’s Electronic Records Express system. No worries, though; an entire client file can easily be downloaded in PDF format, preserving exhibit numbers as bookmarks and all. At least one free application allows users to navigate these PDF files by bookmarked exhibits. And while this particular app can make keeping track of page numbers within an exhibit tricky, my understanding is that there are even programs that can stamp this information on the documents themselves.

Dictation software

The main advantage of using dictation software on a portable device for note-taking purposes, besides portability, is the sheer speed at which notes can be added. Simply put, people can speak much faster than they can type, especially in this case where the user is mostly just paraphrasing or copying relevant doctors notes verbatim.

The main drawback to dictating notes as opposed to typing them obviously involves accuracy. Even a good dictation program is going to mishear some words or phrases as you speak them, though I’m consistently impressed with the extensive vocabulary of medical terminology in the program I currently use. If you’re a perfectionist about your notes, dictation might not be for you. For me, however, I go in with the understanding that the notes I’m taking are essentially for my own eyes only and that I’ll correct any obvious and important errors as I go.

“Dual-wielding”

To avoid the hassle and lost time of switching between the two different apps on one device, in my review method I take my iPad (document viewer) in one hand and my cellphone (dictation device) in the other and “dual-wield” them- to borrow a term from FPS gaming parlance. Besides the benefits already detailed above, this method of note-taking allows me to get away from the desk and stand/pace while I work, an activity scientifically shown to improve critical thinking.

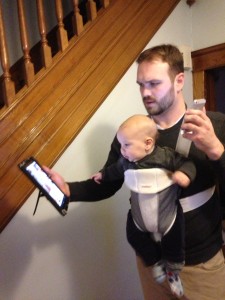

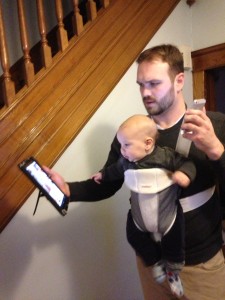

While I don’t personally endorse the idea of dividing one’s attention while reviewing a client’s file, a reality of an associate’s work at a volume practice is that you will need to take work home with you. My method is therefore also great for the multi-taskers out there, as you could easily relax at home and review a file with say, the TV on in the background. You could even use this method to multitask as well as work on your feet; I’ve never actually tried it but I bet you could do this while walking on an exercise bike or treadmill. In fact, as you can see here, I’m currently using this method to show the ropes to the new Junior Partner over here at Smith & Smith.

While I don’t personally endorse the idea of dividing one’s attention while reviewing a client’s file, a reality of an associate’s work at a volume practice is that you will need to take work home with you. My method is therefore also great for the multi-taskers out there, as you could easily relax at home and review a file with say, the TV on in the background. You could even use this method to multitask as well as work on your feet; I’ve never actually tried it but I bet you could do this while walking on an exercise bike or treadmill. In fact, as you can see here, I’m currently using this method to show the ropes to the new Junior Partner over here at Smith & Smith.

That’s all for now. Feel free to comment with any thoughts/questions.